Dirt is ancient, alive, and essential to agriculture. But it is not necessarily eternal. And that can be a big problem.

Dirt is ancient, alive, and essential to agriculture. But it is not necessarily eternal. And that can be a big problem.

Deborah Koons GarciaCalifornia's soil--and the people who study and work with it--plays a large part in Symphony of the Soil, but filmmaker Deborah Koons Garcia says that's not just because the Golden State is her home.

Deborah Koons GarciaCalifornia's soil--and the people who study and work with it--plays a large part in Symphony of the Soil, but filmmaker Deborah Koons Garcia says that's not just because the Golden State is her home.

Half a century ago, the innovations of technology and chemistry that enabled big jumps in agricultural productivity were lauded as the "green revolution." Now, however, says Garcia, the consequences of some of those practices are seen as unfortunately detrimental, especially as used by big agribusinesses, and small-scale methodologies are re-emerging as more cost-effective and sustainable alternatives.

Half a century ago, the innovations of technology and chemistry that enabled big jumps in agricultural productivity were lauded as the "green revolution." Now, however, says Garcia, the consequences of some of those practices are seen as unfortunately detrimental, especially as used by big agribusinesses, and small-scale methodologies are re-emerging as more cost-effective and sustainable alternatives.

Symphony of the Soil will get a premiere screening Monday evening, July 30 at 7 pm in Sonoma State University's Person Theater, as part of the US Biochar conference.

In centuries past, it helped the Indians of the Amazon basin feed their people for hundreds, maybe even thousands of years before the first Spaniards arrived. Now bio-char could help the 21st century world curtail a major cause of global climate change.

In centuries past, it helped the Indians of the Amazon basin feed their people for hundreds, maybe even thousands of years before the first Spaniards arrived. Now bio-char could help the 21st century world curtail a major cause of global climate change.

The key to the benefits of biochar, explains Raymund Gallian of the Sonoma Biochar Initiative, lies in the chemical process of partial combustion.

The key to the benefits of biochar, explains Raymund Gallian of the Sonoma Biochar Initiative, lies in the chemical process of partial combustion.

Although it was only discovered in the past few decades, biochar was actually invented, as much as thousands of years earlier, by the native people of the Amazon basin.

Although it was only discovered in the past few decades, biochar was actually invented, as much as thousands of years earlier, by the native people of the Amazon basin.

Sonoma County and the Sonoma Biochar Initiative are taking a lead role in exploring the modern uses of biochar, which Gallian says is only appropriate, given this area's progressive response to concerns over climate change.

Sonoma County and the Sonoma Biochar Initiative are taking a lead role in exploring the modern uses of biochar, which Gallian says is only appropriate, given this area's progressive response to concerns over climate change.

It’s summertime and the livin is easy. But not if you’re a wine country salmon or trout. Summer is dangerous for young fish. Ted Grantham, a researcher at the University of California, Davis, and his colleagues spent nine years counting young steelhead in streams and pools along Maacama, Green Valley, Mark West and Santa Rosa Creeks. What they found was sobering: On average, across the areas they sampled, about 30 percent of the fish present in early summer lasted through the season. During bad water years and in highly developed areas that number could be much lower. Vineyard managers and other water users, Grantham says, should change how they collect and use throughout the year. If they do, we can have our fish and our wine too.

It’s summertime and the livin is easy. But not if you’re a wine country salmon or trout. Summer is dangerous for young fish. Ted Grantham, a researcher at the University of California, Davis, and his colleagues spent nine years counting young steelhead in streams and pools along Maacama, Green Valley, Mark West and Santa Rosa Creeks. What they found was sobering: On average, across the areas they sampled, about 30 percent of the fish present in early summer lasted through the season. During bad water years and in highly developed areas that number could be much lower. Vineyard managers and other water users, Grantham says, should change how they collect and use throughout the year. If they do, we can have our fish and our wine too.

Cadd originally installed the sensors because he wanted to know if his operations were affecting fish. For his land it doesn’t look like they are. He sits on an aquifer and its levels aren’t directly related to the water levels in the stream, he says. Cadd, a former president of the Russian River Property Owners Association, is involved in a lawsuit against the State Water Resources Control Board, which in 2009 drastically restricted pumping water for frost protection. However the lawsuit goes, he plans to continue collecting data for his own peace of mind.

Cadd originally installed the sensors because he wanted to know if his operations were affecting fish. For his land it doesn’t look like they are. He sits on an aquifer and its levels aren’t directly related to the water levels in the stream, he says. Cadd, a former president of the Russian River Property Owners Association, is involved in a lawsuit against the State Water Resources Control Board, which in 2009 drastically restricted pumping water for frost protection. However the lawsuit goes, he plans to continue collecting data for his own peace of mind.

The data set compiled by Ted Grantham and his co-authors for the study recently published in Transactions of the American Fisheries Society is unique. Here he discusses how they got their information.

The data set compiled by Ted Grantham and his co-authors for the study recently published in Transactions of the American Fisheries Society is unique. Here he discusses how they got their information.

Images: 1) Roger Tabor (USFWS)/Flickr; 2) Danielle Venton; 3) Peter Stetson/Flickr.

Corporations don't eat, breathe, sleep or die—nor even pay taxes in some cases, yet legally they enjoy many of the important Constitutional rights accorded to people. Some actual people are working to change that.

Corporations don't eat, breathe, sleep or die—nor even pay taxes in some cases, yet legally they enjoy many of the important Constitutional rights accorded to people. Some actual people are working to change that.

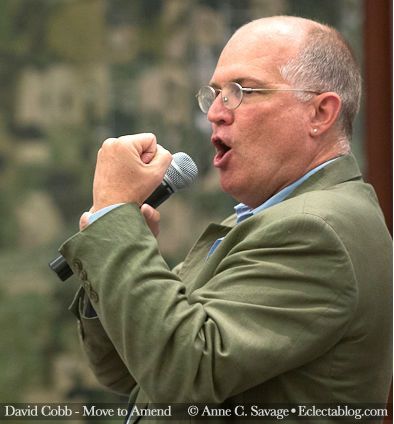

Multinational corporations are the antithesis of local and sustainable, argues Move To Amend founder David Cobb. That's one reason the campaign to undo corporate personhood has been designed to start as locally as possible.

Multinational corporations are the antithesis of local and sustainable, argues Move To Amend founder David Cobb. That's one reason the campaign to undo corporate personhood has been designed to start as locally as possible.

By design, corporations are meant to function as simple-minded, amoral entities, adds Abraham Entin, director of the North Bay chapter of Move to Amend. That, too, is entirely at odds with appropriate human behavior.

By design, corporations are meant to function as simple-minded, amoral entities, adds Abraham Entin, director of the North Bay chapter of Move to Amend. That, too, is entirely at odds with appropriate human behavior.

Occupy Santa Rosa is hosting a "Corporations Are Not People" teach-in on Thursday, July 26, 7-9 pm, in Courthouse Square. David Cobb will be the featured speaker. Admission is free.

Irrigation with treated wastewater has been common on the Santa Rosa Plain since the 1980s, and may soon spread across much of the rest of California. But persistent concerns about the presence of minute amounts of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on that water just got a boost from an important new study.

Irrigation with treated wastewater has been common on the Santa Rosa Plain since the 1980s, and may soon spread across much of the rest of California. But persistent concerns about the presence of minute amounts of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on that water just got a boost from an important new study.

Virtually all testing of chemicals to establish "safe" levels of human exposure uses the same principle: find a minimum amount that can be shown to cause harm, and restrict higher exposures. Anything below that minimum amount is presumed to be OK. But his approach, often characterized as "the dose makes the poison," doesn't work for endocrine disrupting chemicals, explains Dr. John Peterson Meyers, the founder and chief scientist of Environmental Health Sciences, because those substances have different effects at low doses.

Virtually all testing of chemicals to establish "safe" levels of human exposure uses the same principle: find a minimum amount that can be shown to cause harm, and restrict higher exposures. Anything below that minimum amount is presumed to be OK. But his approach, often characterized as "the dose makes the poison," doesn't work for endocrine disrupting chemicals, explains Dr. John Peterson Meyers, the founder and chief scientist of Environmental Health Sciences, because those substances have different effects at low doses.

Brenda Adelman, chair of the Russian River Watershed Protection Committee, is among those who have been raising this issue as applied to the irrigation spraying of Santa Rosa's highly treated wastewater. With this new confirmation of the possible hazards from a team of respected scientists, she is even more alarmed by the state's impending move to expand programs such as Santa Rosa's, especially during the summer months.

Brenda Adelman, chair of the Russian River Watershed Protection Committee, is among those who have been raising this issue as applied to the irrigation spraying of Santa Rosa's highly treated wastewater. With this new confirmation of the possible hazards from a team of respected scientists, she is even more alarmed by the state's impending move to expand programs such as Santa Rosa's, especially during the summer months.

Dr. Laura N. Vanderberg, lead author of the rpraer on testing for environmental chemicals, has also expressed her concerns about Calfiornia's watewater irrigation plans, and the level of water testing to be employed. You can read a summary of the authors' research findings here.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals can be found in a wide variety of common household products, such as those shown at the lef. You can find a lengthy list of the potentially hazardous chenmicals to watch for in such products here.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals can be found in a wide variety of common household products, such as those shown at the lef. You can find a lengthy list of the potentially hazardous chenmicals to watch for in such products here.

Live Radio

Live Radio