photo credit: Brian Wen

photo credit: Brian WenSome of the food Gabriel Biddler received on a recent visit

to his area's food bank. In Sonoma County, the Redwood Empire

Food Bank offers many distribution sites.

On a hot morning in late June, Gabriel Biddler came to River City Food Bank’s distribution center in Sacramento’s Arden-Arcade neighborhood in his wheelchair and with his dog.

He stocked up on non-perishables like soup, pre-cooked chicken and macaroni, as well as fresh carrots, celery, asparagus, tomatoes and bananas. Because of disabling scoliosis, Biddler said, most of his money goes to medical bills, leaving little for food.

“The line, it was never long. Not like this,” she said.

Food banks expect lines to grow even longer, after Congress approved a $186 billion cut to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in early July, the largest cut in the food stamp program’s history.

Though SNAP does not fund food banks, it is a vital safety net. Feeding America, the largest food bank network in the U.S. says SNAP can cover nine meals for every meal a food bank provides.

SNAP cuts will have “devastating consequences,” said Amanda McCarthy, River City Food Bank executive director. She anticipates an increase in first-time clients when SNAP recipients lose their benefits. And she foresees higher demand for more expensive items such as fresh produce, protein-intensive foods, baby formula, and diapers.

“We cannot do it alone,” McCarthy said. “We will need broad-based community support to prevent hunger from becoming an even deeper crisis.”

River City Food Bank is in a better position than some other California food banks whose federal grants and subsidies have disappeared in the past few months.

The Food Bank of Contra Costa & Solano distributes 2.7 million meals every month to residents in those counties. It is pressed to meet that demand after losing over $2.2 million in promised federal grants. In addition, 11 truckloads of food shipments through the federal Emergency Food Assistance Program were canceled — 250,000 meals that could have reached 65,000 households, said Jeremy Crittenden, a spokesperson for the food bank. That program has been a crucial source of fresh protein, one of the costliest and most demanded food groups.

In San Francisco, the city’s largest provider, the San Francisco-Marin Food Bank, recently shut down more than 20 pop-up pantries launched during the COVID-19 pandemic after losing local funding.

“We’re dealing with a perfect storm of food insecurity,” said Marchon Tatmon, the food bank’s director of policy.

Tatmon said the food bank is already stretched thin, with 8,300 people on a waitlist that is expected to grow as people lose their federal benefits. And filling those gaps could be even harder, with federal funding cuts to food banks likely on the way.

More than 109,000 San Franciscans are enrolled tin CalFresh, which distributes SNAP benefits through an electronic credit system in California. Many stand to lose benefits under the new federal legislation, with deeper cuts possible in two years when the state will be forced to cover part of the program’s food and administrative costs.

Tatmon fears these cuts will worsen already unprecedented food insecurity in San Francisco, with a 2023 report finding more than 116,000 residents struggling to access food.

“What’s happening at the federal level will only amplify what we’re seeing locally,” Tatmon added.

For the Contra Costa & Solano Food Bank, the largest loss has been a $1.9 million grant from the Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Agreement Program that was terminated in March. The grant enabled the food bank to purchase fresh produce directly from local farmers.

Caitlin Sly, the food bank’s president and CEO, called it a double benefit — providing fresh food to those in need and supporting local farmers. Through the grant, the organization also could better serve culturally diverse communities.

“We were able to buy cilantro and bok choy and mushrooms and collard greens, some things beyond potatoes.” she said.

California food banks are soliciting contributions on social media and in direct appeals to donors, as they assess their losses. For some, resources have been strained since the pandemic, when demand for food services surged. It has yet to wane. In 2022, more than 1 in 5 California households were food insecure, according to the Association of Food Banks.

Sly’s group worries that the heightened threat of immigration enforcement across the country will make even more people food insecure. To provide services to immigrants who might be afraid to leave the house to go to work or the grocery store, Contra Costa & Solano Food Bank has set up four refrigerated food lockers in the East Bay, with a fifth under construction.

Contra Costa County funded the lockers, which are at community colleges and a church. People order food online and pick it up at a time they choose.

“You could go in the middle of the night if you wanted,” Sly said. “And so, it's a more private way of getting food.”

The food bank, she said, is trying not only reach immigrant communities but also reassure them that others care about their well-being.

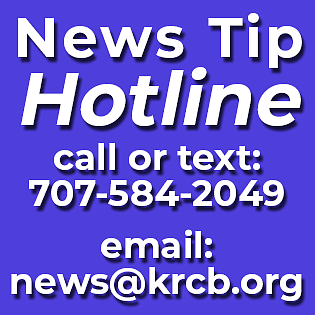

Bryan Wen is a student at UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism; Zhe Wu is a California Local News fellow at the San Francisco Public Press. This story was co-published with KRCB/Northern California Public Media and is part of “The Stakes,” a UC Berkeley Journalism project focusing on executive orders and actions affecting Californians and their communities.

Live Radio

Live Radio